|

Is it time to start chopping your supply chain up? Perhaps so.

If you have been paying much attention to the latest supply chain thinking, you may have noticed that there is a lot of emphasis lately on "segmenting supply chains," or some related concept.

Gilmore Says: |

There is clearly common sense in all this: one size very rarely fits all; different customers or products clearly do have different supply chain success requirements. There is clearly common sense in all this: one size very rarely fits all; different customers or products clearly do have different supply chain success requirements.

Click Here to See

Reader Feedback

|

What does that mean? Pretty simply, it means that a company rarely has just a single supply chain - even though it may think it does. Rather, a company has multiple supply chains based on a variety of mostly customer-driven factors, and that supply chain organizations must define and execute those different supply chains in different ways, logically enough. I will explain that more in a few paragraphs.

"Segmenting supply chains" is currently a major area of research and analysis from Gartner. Dr. David Simchi-Levi of MIT focused a good portion of his excellent book Operations Rules on the subject. As we detailed in a ground-breaking Videocast earlier this year, a key element of Dell's supply chain transformation over the past two years was segmenting its supply chain to meet the different market needs of its traditional make-to-order supply chain and its much newer retail store channel market. Dell in fact was helped in its new strategy by Simchi-Levi.

This is hardly a new concept. In 1997, Marshall Fisher of the Wharton Business School wrote an article for Harvard Business Review on What is the Right Supply Chain for Your Product?

He said that "The first step in devising an effective supply-chain strategy is therefore to consider the nature of the demand for the products one’s company supplies... I have found that if one classifies products on the basis of their demand patterns, they fall into one of two categories: they are either primarily functional or primarily innovative. And each category requires a distinctly different kind of supply chain. The root cause of the problems plaguing many supply chains is a mismatch between the type of product and the type of supply chain."

In the early 2000s, the consultants at AT Kearney wrote a white paper called How Many Supply Chains do You Need,? which I believe was also turned into an article for Supply Chain Management Review, but we couldn't find it after a medium amount of effort (white paper is here).

In that white paper, Kearney noted that while most recognize the different supply chain needs of different industry sectors (say grocery versus apparel), many individual companies fail to recognize they have such differences within the different products and markets they have within their own enterprises.

Kearney added that "choosing the right chain for the right business requires strategically thinking about how your business operates and what your company needs, which includes how many supply chains it takes to serve your customers."

But from that point until fairly recently, the subject seems to have somewhat disappeared from the overall supply chain dialog, only to resurface more recently.

Why? Maybe the thinking was too early for its time, which happens often in this discipline. Or from the different side of the coin, while the concept was valid, technology just wasn't ready to well support its execution.

I would also say that growing supply chain complexity has made the concept more pressing than before. That would include globalization (emerging versus developed versus in-between markets), multi-channel strategies, the increased size of many companies from mergers and acquisitions (resulting in new products, markets and channels to the company), and other changes.

The bottom line is that there is a growing consensus from the pundits that a "one size fits all" supply chain won't cut it anymore. And I agree.

In Operations Rules, Simchi-Levi noted that common segmentation attributes include customer value proposition (e.g., value versus innovation, similar in a sense to Fisher's perspective), market channels, product characteristics such a demand uncertainty and logistics costs, and more. Among many other considerations, Simchi-Levi observed that perhaps the key decision that needs to be made based on those attributes is whether to construct an individual supply chain using a "push" strategy, a "pull" strategy," or hybrid push-pull approach.

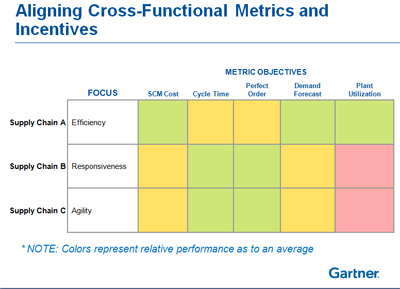

Gartner's Matt Davis, who worked at Dell before moving to Gartner, said during another Videocast we produced within the past month or so that different market segments tend to value either cost, responsiveness/speed, or level of service/agility, and that supply chains should often be segmented accordingly.

Key there he said is differentiating performance metrics: if you build a supply chain focused on agility for one group of customers, you can't expect the same type of cost performance for a supply chain that is built primarily to minimize cost. An iron law of supply chain is that such trade-offs can't be eliminated. I will agree many companies forget this.

He used the chart below to illustrate this, which is worth considering.

View Full Size Image

Then there is the perspective of Dr. John Gattorna, based in both Australia and the UK, who also argued in his book Dynamic Supply Chains that customers and hence supply chains should be segmented based on what they value from you as a supplier, but with a unique twist.

He identified four "metatypes" for such a segmentation based on a customer's buying behaviors. That includes some notion of how much different segments are interested in collaborating:

(1) Continuous Replenishment: Predictable demand, a lot of collaboration

(2) Lean: Focus on supply chain efficiency

(3) Agile: Pull-oriented supply chains to meet unpredictable demand

(4) Fully Flexible: Sort of an agile supply chain on steroids; some maintenance and repair operations come to mind

What somewhat differentiates Gattorna's view is that he notes that a given customer may have several of these buying behaviors operating at once, complicating matters for suppliers, and that a customer's needs for a given product may change over time - in fact likely will. Simchi-Levi says similar things, though from a somewhat different framework.

There is clearly common sense in all this: one size very rarely fits all; different customers or products clearly do have different supply chain success requirements.

One question I have had though is how far can you/should you really take this. Can't you wind up with too many "supply chains", and tremendous complexity that overwhelms the potential benefits?

Simchi-Levi says the key is to find synergies across these multiple supply chains. For example, Dell shared much (but not all) of its physical logistics infrastructure between its make-to-order and retail supply chains even as they differed in many other respects, reducing overall complexity and costs.

Davis says that while that if you think you have just one supply chain you are most certainly wrong, if you think you have more than 4-5 you are over complicating the analysis.

I have to say that a recent video interview we did with Kelly Thomas of JDA Software on this subject just a few weeks ago helped me think this through quite a bit.

He made a couple of key points. (1) The reason the subject of segmenting supply chains is on the rise now is because when the topic was first promoted more than a decade ago, it often meant different physical supply chains, which were too expensive. Now, software advances can enable differentiated supply chains in a "virtual" way so that such segmentation is affordable.

(2) A high percentage - maybe 30-40% - of a company's products and customers are not profitable. What supply chain segmentation can do is make many of those customers and products profitable.

This gets into the area of Service Policy Optimization, which I have been meaning to write about literally for years. I also believe all of this is in the end related to Procter & Gamble CSCMP announcement that it is now measuring its supply chain performance by how its customers measurer P&G.

How's that for an ending tease? More on both those topics, and really sorting all this out, very soon.

Do you well understand the concept of supply chain segmentation? Is it real? Is anyone actually doing it yet? What would you add to Gilmore's analysis? Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below.

|