|

For just about my whole supply chain life, and certainly since the late 1990s, I have been hearing calls for additional investment in logistics US infrastructure: roads, rails, ports, etc. The message: we need both to fix much of what we have, and also to add a lot more of it.

Those infrastructure worries and calls for action reached a crescendo in 2007, as the wave of imports put a lot of pressure on our logistics capacity, and the collapse of a major bridge in St. Paul sent the message that much of the existing infrastructure was literally crumbling.

But how much, if any, is too much investment in infrastructure? (I will explain that below.) And what really should be the priorities, given that there is no way we can do it all? (Only China seems to be able to manage that – paid for by the tidal wave of trade surpluses.)

On top of those questions, of course, is the fact that we have seen dramatic decreases in the movement of containers and freight here in the recession, which has been more like a depression when it comes to logistics. So, in the short term, the infrastructure situation isn’t exactly a burning issue any more – though many say trouble is again headed our way.

Gilmore Says: |

At some point, for any individual company, or a country as a whole, the benefits from better logistics infrastructure start to outweigh the additional costs to pay for it. At some point, for any individual company, or a country as a whole, the benefits from better logistics infrastructure start to outweigh the additional costs to pay for it.

Click Here to See

Reader Feedback

|

I got on this question back in the Spring, at the NASSTRAC conference in Orlando, where one of the group’s leaders noted that the logistics industry (carriers and shippers) were likely to be on the hook for much of the financing of any major infrastructure improvements. His message – be careful what you wish for.

Before we look at that though, it is not hard to find people articulating the problem.

My new friend George Stalk of Boston Consulting Group recently wrote in the Harvard Business Review that “As our worldwide transportation network becomes less and less able to support the demands of a global economy, we’re heading straight into a crisis,” arguing that we shouldn’t let the current freight slowdown blind us from mid-term needs.

He notes, among many data points, that since 1990, US vehicle mile traffic has increased some 41%, while highway “lane miles” have increased just 5%. That obviously means increasing congestion for cars and trucks. There are similar data for ports and rail.

Many say that the issue is beyond just a matter of increasing logistics costs for shippers – that the quality of logistics infrastructure will increasingly be a determinant of a nation’s overall economic competitiveness. In that light, it’s not surprising that China has many of the world’s most sufficient ports, and is spending billions on roads and waterways.

However, it will take lots and lots of money to address these issues. Just how much, you ask?

In 2008, the National Surface Transportation and Revenue Study Commission, a Congressionally sponsored effort, recommended that funding for logistics infrastructure over current investment projections be increased to the tune of almost $200 billion dollars through 2020. That’s a lot of money.

That report, in part, recommended additional gasoline taxes to generate the funds. Less reported was the fact that the commission also vaguely called for more taxes from truckers/shippers that would result in a more proportional amount of revenue to be generated versus their use/benefit of the highway system.

And there, in fact, is the rub, and what I have been thinking about for the last several months: there is no free lunch. Some experts, for example, call for the trucking industry to incur a “Vehicle Mile Tax,” or VMT – a charge per mile driven, in addition to any taxes on diesel fuel.

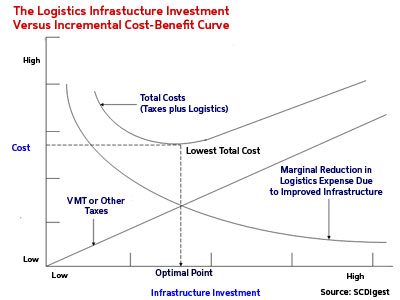

We can agree that improved logistics infrastructure is a good thing; but the question becomes, at what point does the incremental cost in terms of new taxes to pay for it begin to outweigh the incremental benefit in terms of lower logistics costs?

As you will see below, I took a traditional supply chain trade-off curve, such as inventory versus logistics costs, and reconfigured it for logistics costs versus increased taxes.

Larger/downloadable Version

The summary idea behind the graph is this: at some point, for any individual company, or a country as a whole, the benefits from better logistics infrastructure start to outweigh the additional costs to pay for it. For any company or the country, there is an optimal point that minimizes total cost: logistics costs (which we can assume should decline as a result of improved infrastructure, or why do it?) plus additional taxes.

Where that point is on a national scale, I have no idea. And because it is likely that we will only get a fraction of the money many say we need to devote to infrastructure, we may not get anywhere close to passing the point of diminishing returns.

But that then begs the question: how should money that becomes available best be spent? I have had a hard time finding anyone with an answer to that question. More on that soon.

The main point again is just that when we hear the calls for billions for infrastructure, much of the money will likely in the end come from shippers (as it already has in new containers fees at some ports – usually under protest from shippers, it should be noted.) I think the concept of some “optimal point” is one worth thinking about, as are companies considering their own cost curves versus additional taxes.

I also realize, as noted above, that there are national competitiveness questions here too that some may argue should trump a given company’s own cost picture.

So, as my friend Gene Tyndall likes to say, these are the questions. I think they are worth pondering. |