From SCDigest's OnTarget e-Magazine

- July 9, 2012 -

Logistics News: Undercover DC Worker Says Job Amounts to Being a "Warehouse Wage Slave"

Walking 12 Miles a Day, and Getting Bad Shocks in the Book Section, Reporter Says; Probably Could Keep Job if She Could Get Used to Hearing How Bad She Is

SCDigest Editorial Staff

We've seen a couple of CEOs find out what life is like working in one of their company's distribution centers as "Undercover Bosses"on the hit CBS television show (and it's much harder than they thought, of course). (See Undercover Boss Hits the Distribution Center for the Second Time, and Paints a Lousy Picture of Work in the Warehouse.)

Now, a reporter for Mother Jones magazine infiltrates another e-commerce distribution center as a regular floor associate for an article she is working on - and you probably won't be surprised that she doesn't like the work. Below, we summarize her report, which is very critical of the life of a DC associate. We are covering her views and report, not necessarily SCDigest's own.

SCDigest Says: |

|

| "We will be fired if we say we just can't or won't get better," one temp tells her. "But so long as I resign myself to hearing how inadequate I am on a regular basis, I can keep this job," she says.

|

|

What Do You Say?

|

|

|

|

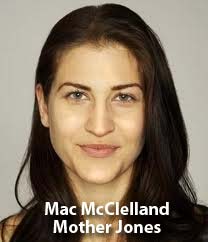

Mac McClelland, a human rights reporter for the magazine that is generally recognized as being on the far left of the political spectrum, tells her saga in a recent article titled "I Was a Warehouse Wage Slave," which recounts her time in an anonymous warehouse after she had applied for the job and got hired as a temp worker just like anyone else might. She kept the actual company anonymous, because, McClelland says, "to do otherwise might give people the impression that these conditions apply only to one warehouse or one company. Which they don't."

It turns out McClelland has worked in distribution centers just as part of her job history earlier in life, and authored a previous article about a temp job at another e-fulfillment center, where she says she labored "under conditions that were surprisingly demoralizing and dehumanizing, even to someone who's spent a lot of time working in warehouses, which I have."

This position for this latest article, for a very large company she tags with the alias Amalgamated Product Giant Shipping Worldwide, is in a small town somewhere west of the Mississippi (though it seems pretty obvious to us what company this is). Most everyone in the town either has worked there or knows family or friends that do.

Someone from the town's Chamber of Commerce tells her before she starts the job that working conditions are going to be far from pleasant.

"They need you to work as fast as possible to push out as much as they can as fast as they can. So they're gonna give you goals, and then you know what? If you make those goals, they're gonna increase the goals. But they'll be yelling at you all the time," the woman tells McClelland.

She adds: "It's like the military. They have to break you down so they can turn you into what they want you to be. So they're going to tell you, 'You're not good enough, you're not good enough, you're not good enough,' to make you work harder."

And finally, the Chamber staff person recommends this: "Don't say, 'This is the best I can do.' Say, 'I'll try,' even if you know you can't do it. Because if you say, 'This is the best I can do,' they'll let you go. They hire and fire constantly, every day. You'll see people dropping all around you. But don't take it personally and break down or start crying when they yell at you."

Despite having written that previous article, she is hired through a staffing agency rather easily, other than needing "to confirm 20 or 30 times that I had not been to prison." Despite having written that previous article, she is hired through a staffing agency rather easily, other than needing "to confirm 20 or 30 times that I had not been to prison."

A computer program asks her a series of questions, including confirming that she can read by entering the name of Michael's Jackson's Thriller album from an image of its cover, and making sure to ask that she is not especially interested in "dangerous activities".

McClelland was being hired for the Christmas season last year, and is told she will be working mandatory 10-hour days (later 12 hours), and that stretching will also be mandatory to help avoid injuries. A $500 bonus will be given to employees who identify a co-worker who has filed a false worker's comp claim and that person is convicted. She will make 11 dollars and change per hour.

As she starts her first day, one worker tells her that she must avoid crying when supervisors yell at her. Can she really be fired for crying, she wonders?

"Yes," the worker responds. "There's 16 other people who want your job. Why would they keep a person who gets emotional, especially in this economy?"

Exec Acknowledges that the Environment is "Intense"

There are many videos for new workers to watch, McClelland says, including one in which an Amalgamated exec acknowledges that the environment in the DC is "intense," not because the company wants it to be, but because "our customers demand it," McClelland quotes the executive.

She says "We are surrounded by signs that state our productivity goals. Other signs proclaim that a good customer experience, to which our goal-meeting is essential, is the key to growth, and growth is the key to lower prices, which leads to a better customer experience. There is no room for inefficiencies."

After training is finished, which includes many warnings on all the ways workers can be killed or seriously injured, she starts working as an order picker. Amalgamated employs some type of labor management system (LSM), because her wireless device informs McClelland how many seconds it should take for her to arrive at each picking location when she receives the next instruction.

"At 5-foot-9, I've got a decently long stride, and I only cover the 20 steps and locate the exact shelving unit in the allotted time if I don't hesitate for one second or get lost or take a drink of water before heading in the right direction as fast as I can walk or even occasionally jog," McClelland writes. "Often as not, I miss my time target."

She finds some strange processes. If she is directed to a location and the item is not there, she says the system makes her scan every other item in the bin location to prove it. This process is supposed to take just seconds, according to the LMS, when it in fact takes much longer, really hurting herperformance if she get very many of these scenarios in a day.

In what is a new phenomenon to us here, as workers race to the break room for their 15 minute breaks, they must stand in line to go through a metal detector, to make sure they haven't shoved something from the DC down their pants.

Between that and using the restroom, she figures she and others get about 7 of the 15 minutes as an actual break, during which she "inhales as many high-fat and -protein snacks as I can."

She notes running back to your position from the break sometimes allows a few brief seconds of conversation - which is better than the previous DC she wrote about, where you could be fired for having conversations with other employees.

There is some type of metal bars in front of a lift that takes pickers and their carts up to the second and third floor picking areas that are dangerous. "Within the last month, three different people have needed stitches in the head after being clocked by these big metal bars, so it's dangerous," McClelland reports "Especially the lift in the Dallas sector, whose bar has been installed wrong, so it is extra prone to falling, they tell us. Be careful."

She says the company estimates she will walk about 12 miles per day on the concrete DC floors. McClelland also finds the frequent need to bend down to the lowest level for picking to be especially hard on her body. She wonders whether this is cool with OSHA. Turns out it is, she later finds, as OSHA doesn't have ergonomic standards that don't directly impact safety.

(RFID and AIDC Story Continued Below)

|