|

While we have covered supply chain risk management issues many times in our regular articles, to the best of my memory I have never dealt with the subject directly in this column. (As an aside, to see what we have done, go to www.scdigest.com, select "Search by Topic" in the top of the page, select "Supply Chain Risk" - you can find lots of good stuff that way.)

Gilmore Says: |

The Risk Exposure Index can be overlaid on supply chain network design alternatives - and eventually integrated right into related software tools - to better show the tradeoffs between cost, service and now risk. The Risk Exposure Index can be overlaid on supply chain network design alternatives - and eventually integrated right into related software tools - to better show the tradeoffs between cost, service and now risk.

Click Here to See

Reader Feedback |

Well, that topic is overdue, and you will find it here this week for a very good reason - we had two independent but equally fantastic Videocasts on the subject this week, and I think you will enjoy the summaries.

I am going to discuss the second broadcast first because some important supply chain news came out of it. My friend Dr. David Simchi-Levi of MIT - truly one of the best supply chain thinkers we have today, a perpetual motion machine of ideas - announced during the broadcast an exciting new way to measure supply chain risk. He calls it the Risk Exposure Index, and it addresses one of the issues that has vexed me for a long time: we seemed to have very little ability to actually quantify supply chain risk.

Most companies seem to be stuck on simply categorizing risk along two dimensions, such as probability of occurrence and the size of impact were a particular disruption to occur. Because that's the best we have had. This approach has at least two issues: (1) there was no quantification of the impact, so how much a company might invest to mitigate a given risk remained something of a guessing game; (2) it almost by definition looks at risk as independent individual events, and does not really consider the issue from a full supply chain context.

Enter the new Risk Exposure Index. A key concept here is what Simchi-Levi calls Time to Recovery, or TTR. This refers to how long it would take a company to fully recover from a major disruption, such as by ramping up production elsewhere, finding new sources of supply, changing out materials, or other means. That in turn leads to calculation of the Financial Impact (FI) of the disruption through its TTR.

Another key concept is "unknown unknown" risks, which is really what the Risk Exposure Index is designed to address. Risks like demand fluctuations and lead time variability present risk, Simchi-Levis says, but can be modeled and therefore well addressed. But the unpredictable risks are a much tougher game.

We tend to think of unknown unknown risks in terms of natural disasters, especially after the Japan earthquake/tsunami and Thailand floods in 2011. But it includes a lot of other utterly unpredictable sources of disruptions as well, such as a fire at a factory or the political uprisings in the Middle East last year.

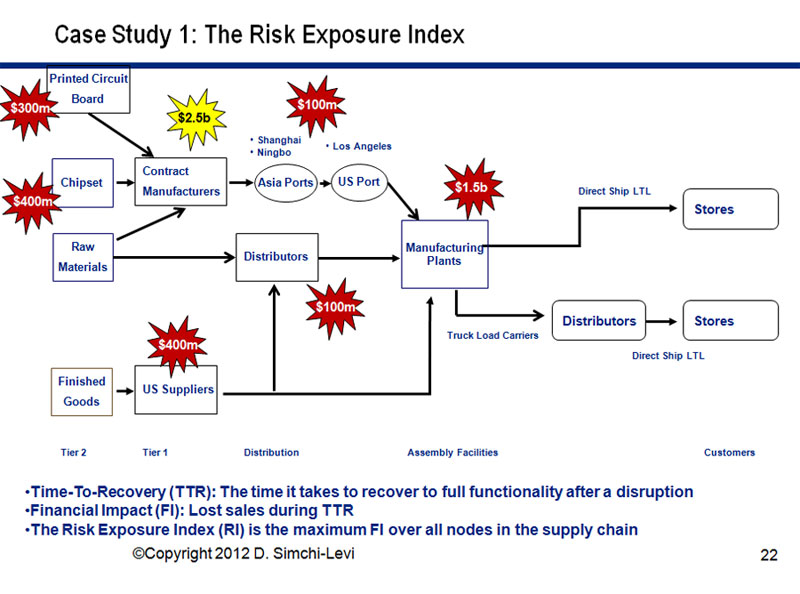

So you put all that together, and you get the following risk model:

The numbers in the red stars represent the Financial Impact for different elements of a given value chain in the high tech industry (based on work Simchi-Levi did for a major company in the industry late last year). The $2.5 billion number in yellow indicates the full financial impact if the entire chain was disrupted for the maximum TTR.

I obviously can't do full justice to the details of the Risk Exposure Index in just these few paragraphs, but it seems to solve two of the issues noted above: It does provide a very clear way to quantify supply chain risk, and it also takes a full supply chain view of the level of risk.

One thing you might quickly deduce: this analysis will often lead companies to reduce TTR and/or FI by improving supply chain flexibility. Also, the Risk Exposure Index can be overlaid on supply chain network design alternatives - and eventually integrated right into related software tools - to better show the tradeoffs between cost, service and now risk.

I have not seen anything quite like it in this area. After the broadcast Wednesday, Simchi-Levi was flying off from Boston to Europe to introduce the concept to a major company over there. You can watch an on-demand version of the broadcast, download the slides, or listen to a podcast of the excellent Q&A session here: New Supply Chain Risk Exposure Index Videocast.

If that wasn't enough, we had another outstanding Videocast on Tuesday on Managing Risk in Multi-Tier Supply Chains, featuring Dr. Tom Choi of Arizona State University, Tom Linton, who is SVP and Chief Procurement Officer at Flextronics, and Rich Becks, who heads up the high tech group at software provider E2open.

The broadcast was based on and actually extended an article Choi and Linton had published in the Harvard Business Review in December in 2011, which I confess I had managed to miss (I usually review each issue of HBR).

The core message is this: far too many companies are giving up too much responsibility and control to first tier suppliers, to their peril. It is important, said Choi, that companies not "lose control of their bill of materials," and maintain high levels of visibility and often direct control of second and third tier suppliers.

Apple, of course, seems to be a prime and successful example of doing just this, renowned for maintaining strong control over most of its suppliers at each level, but Choi and Linton (who not long ago left a similar position at LG Electronics for Flextronics and is clearly a deep thinker about such issues) say the trend seems to be for many companies to just outsource the management of the lower tiers to the tier 1 suppliers, and then rigorously manage those tier ones.

There are all kinds of benefits for maintaining that multi-level control, they said, especially around reducing risk that in the end also means reducing costs. Linton also noted when at LG, by starting to break through the tier 1 paradigm and working more directly with tier 2 chip manufacturers, LG was able to get a much better and more accurate read in 2009 on where the economy and electronics markets were headed - and made investments and plans for the quick recovery which did in fact materialize when many others were frozen, worried a true depression was coming,

Choi also presented his model of Honda' multi-tier supply chain for a single "module" - the center console for one of its automobiles. Honda is another company that maintains a lot of direct control over many (not not all) tier 2 and 3 suppliers, and Choi did a good job explaining exactly the rational for how such decisions are made.

What also just jumped out at me is that it took Choi three years to build this model, working with Honda and various suppliers. The message to me: companies don't really maintain these sort of multi-tier supply chains maps? Maybe it's time.

One question I had was just how much overhead might this add back in to the organization. The answer seemed to be two-fold: (1) It could add back some, but if smartly done would be well worth it; (2) new tools can provide a level of visibility and process management that can free up existing resources and enable this higher level of control below tier 1 with much greater efficiency than would be possible without such tools, which weren't really available just a few years ago.

This on-demand version of this excellent, the slides, etc., are also all available: Managing Risk in Multi-Tier Supply Chains.

Supply chain may be "risky business," but here were two pretty darn good takes on how to make it a little less so. Good job by all.

What do you think of the supply chain Risk Exposure Index approach? Do you agree too many companies are losing control of their bill of materials? Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below.

|