Anyone with experience with this type of system will have likely have direct knowledge of the problem with the "no scan" method. Those pick quantity errors mean either a shortage in the number of cartons picked for the order that have to be fetched later when the shortage is recognized, or else extra cases that will eventually go down the "reject line" on the sorter. In either scenario, the error is time consuming and costly to correct.

3. Use pick by label: Another approach is to have preprinted carton labels for each set of picks. The picker puts on the labels and places each carton on the belt, moving on to the next location when the labels for a given SKU/pick are exhausted. The downside is that this approach basically defeats the concept of using wireless technology to begin with, and also is a hit to productivity, being roughly as fast (possibly a little faster) than scanning each carton. We will note though that if the cases are not already labeled, pick by label may be necessary to identify the cartons on the sorter.

More recently, other options have emerged. Use of voice technology is one such option. As we will detail on an upcoming white paper on voice technology in distribution, voice may be able to deliver high levels of accuracy with minimal impact to picking efficiency.

In this scenario, pickers would count into their headsets as they picked the cartons. One of several methods would used, such as counting as each carton is picked (1, 2, 3, etc.), or saying "next" or some similar phrase at each pick, having the system keep track of the count. At any time, the picker could ask for where they stood in the count ("You have picked 24 of 33 cases.").

The voice advantage is that it is "hands free," meaning high levels of productivity could be achieved because the count verification is coming through the voice process while the cartons are being placed on to the belt.

Another potential approach that a few companies have used would be to put a fixed scanner(s) along or at the end of the pick belt in each module. This is becoming more feasible because the cost of such scanners has dropped dramatically in recent years.

In this set-up, the warehouse control system (WCS) or possible the WMS itself would receive carton count information as the cases on the pick belt passed by the scanner. If it saw more than expected, one set of actions would take place, perhaps to the level of stopping the pick belt - though some in the material handling industry say that action would cause too many overall system efficiency issues.

If too few cases of a given SKU were seen, there would have to be some communication method to alert pickers or supervisors that such a shortage had occurred. That could be a visual display in the pick module itself, an alert to a supervisor, or some other method.

But the complexity of this "work flow," and the level of integration that would be required between the WMS and WCS, in practice means this is an option very few companies have embraced.

It's worth noting that of course the WCS will do this counting and tracking further downstream, just further downstream on the sorter.

Even there, "The error detection for simple pick-to-belt would be visual only," says Jerry Koch, director, corporate marketing and product management for material handling automation systems provider Intelligrated. "That means the counts would in the most common scenario show up with an over or under on the management screens. We do not stop belts or alarm for manual intervention. The error is handled at the next decision (scanning) point sending any out of wave cartons to an exception lane."

Role for Count-Back?

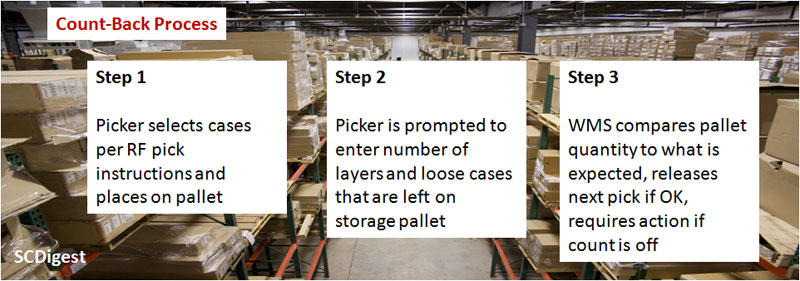

Given all that, is there a role for count-back in the process, especially for those that have made recent investments in RF and for whatever reason are unlikely to make move to voice in the near term?

Possibly.

Count-back could quickly identify when cartons have been under-picked, in time to easily add the missing cartons back on to the belt. Under-picks in the end are far more costly and problematic than over-picks, and these could be almost eliminated using count-back - at least from pallet flow rack pick locations (more on that in a second).

Count-back would identify that over-picks have occurred, but by the time it is largely too late to correct the error - the cartons are already on the belt and moving towards the sorter.

Still, the cycle count would identify the error and re-correct the current case count in the location, needed among other reasons so that the next count-back process is accurate. But the conveyor system might be able to divert extra cartons earlier in the material handling flow for put back into the pick locations, and/or generate an automatic WMS task for doing so, better automating the process than most have in place today.

So, it seems like count-back could be a good thing to solve this pick-to-belt issue, with a couple of caveats:

1. The WMS system again is likely to require modifications to enable count-back.

2. The process works well for full pallets, typically positioned in pallet flow rack lanes in a pick module. It could also work for full pallets stored in reserve areas that are picked via order picker trucks and placed onto a spot on the conveyor system. It could be made to work in "half pallet" storage locations by maintaining a profile of half pallets as well.

But it wouldn't likely work very well in case flow pick lanes, where it may be difficult to see and/or count the number of cases remaining in the location. As many companies only use pallet flow rack for their fastest moving SKUs, and supplement with half-pallet storage and case flow racking for slower moving items, this could be a problem.

However, as said half-pallets could probably be accommodated, and picking errors are much lower when picking just a case or two for slower movers such as those that may be carried in the case flow racking. In other words, even if case flow rack locations could not be accommodated, count-back might still reduce picking errors dramatically in pick-to-belt applications with downstream sortation. An 80% solution may be much better than no solution.

Count-back remains a little understood approach that exists largely still in the food manufacturing sector. While it may not be a panacea for the issues of pick errors in automated systems, it appears to us like it just might be a piece of the puzzle for some companies.

What is your reaction to the use of count-back for pick-to-belt applications, especially in batch pick environments? Why could it or could it not deliver value? How have you addressed this accuracy issue in such systems? Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below.

|