Last summer, I wrote a piece on the “Supply Chain Impact of $100 Oil,” which drew a lot of lively response.

I don’t mean to repeat the topic so soon, but a few accidental discoveries of late have me thinking afresh on the subject. It’s worthwhile for all supply chain and logistics professionals to consider potential issues with energy, to say nothing of all the other economic and political ramifications continually rising energy prices would have.

While reading Forbes magazine’s annual investment, I tripped upon an article about billionaire investor Richard Rainwater. He’s made a literal fortune over the years with some very smart bets, including investing heavily in oil in the 1990s when it got very cheap.

Right now, he’s investing hundreds of millions more.

Most of us haven’t heard of “Hubbert’s Peak.” It was named for Shell geologist named M. King Hubbert, who observed that oil wells/fields have a very predictable output profile, shaped like a bell curve. Annual output increases until half the oil is gone, after which it starts to decline, because the oil at the bottom is harder to get out.

Hubbert used the curve in the 1940s to not only predict output from individual sites, but the U.S. as a whole. He suggested that U.S. domestic oil output would peak sometime in the 1970s. At the time, he was severely criticized. As it later turned out, he was quite correct.

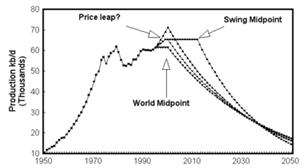

Now, observers that range from well-respected geologists to somewhat crackpot end-of-the-world types are looking at this from a global perspective. Here’s one view, suggesting peak oil production in the next couple of years.

Forbes quotes Rainwater as saying, “In 1988 there were 15 million barrels a day of shut in production [meaning surplus that could be tapped] and the world was using about 55 million barrels of oil. Today, the world is using 80 million, and there is no shut in-production.” “Peak Oil” is another term used to describe this theory – global production is at or near the peak, and will soon move to a long, inevitable decline.

The graphic above is taken from the web site LifeAftertheOilCrash.net. If you’ve never seen it, take a look (it's sometimes overhwelmed though). Rainwater has it at the top of his favorites list. Yes, it’s apocalyptic, end-of-life-as-we know-it stuff, but even if it’s partly right, as an increasingly number of serious observers believe, we could be in for some serious times.

Myself, I am more optimistic. Brazil, for example, has largely eliminated need for any foreign oil through its ethanol vehicle program. As energy expert Peter Huber recently wrote in the Wall Street Journal, the real problem is almost only related to transportation. The “grid” of electricity and natural gas is actually in good shape all told, has true competition among buyers from different energy sources, and can be powered by U.S. domestic energy materials (natural gas, coal and uranium). There also seems to be much promise at these prices for oil from shale and tar, with abundant North American reserves of each.

But will all that happen in time to avoid the big shortage and squeeze? Rainwater says No. He in fact believes the coming energy crisis will produce a “long emergency” that will wreak havoc for years until a better solution emerges.

I am much less worried in the middle-term, believing that technology, ingenuity, and the various alternative fuels will eventually solve the problem (Peter Huber favors vehicles running on natural gas, by the way, which more than I realized are already doing right now).

Bringing it back to supply chain – should you be thinking about what a spike like this might mean? Should our network and supply chain strategies take scenarios of $120 or $200 per barrel oil into account? And how much should you hedge your bets – since there’s always a cost to hedging, and if oil doesn’t spike you’ll pay that price?

I asked Jeff Karrenbauer of Insight (supply chain network planning software), who is known for his thinking about SCM network issues, about this subject. He agreed this possibily changes the game.

“Now, when you're planning, you really have to forecast not just demand but cost,” Karrenbauer told me. “Many companies use static or gradually incrementing cost models, but now you have to think in terms of say 10 discrete one-year periods, and estimate some different cost scenarios across those years and the probabilities of each. At certain levels of the cost of oil and hence transportation, domestic supply sources, for example, start to be the better choice than offshore. So, should I maintain, under current costs, a domestic supplier with say 20% of the volume, so that I can more easily switch back here if transportation costs sky rocket?” (Karrenbauer made a number of other interesting observations we don’t have room for here, but will cover next week in more detail).

I think it’s smart investing to have a reasonable percentage of your portfolio in oil related stocks. And I’d be making sure I understood how my supply chain would most effectively adapt and respond if Richard Rainwater is right.

Are we at "peak oil?" Do we need to start forecasting logistics costs the same way we forecast demand? Are companies doing enough to give themselves options in the future?

|

![]()