7-Eleven Changes Strategy and Delivers Results

Convenience Store chain 7-Eleven provides an interesting case study of a company that achieved significant operational improvements from outsourcing a wide array of functions, many of which were considered “core” before the new strategy was implemented.

Even as a retailer, 7-Eleven was highly vertically integrated, doing almost all of its own distribution of in-store goods, delivering its own gasoline to the pumps, even making some of its own food items. It also was experiencing poor financial results. The chain subsequently embarked on a new strategy over several years, leading to a substantial project to re-think its value chain. This ultimately included shedding in-house functions through outsourcing or collaborating with suppliers for dozens of activities formerly performed internally.

The Two Questions

The process started by identification of what really drove results for the chain: the answer was merchandising, or the pricing, promotion and positioning of in-store items and gasoline. All other activities were on the table at 7-Eleven for outsourcing or partnership.

“In deciding what to outsource and what to keep inside, “ the HBR authors wrote, “7-Eleven considered two factors: whether a capability was proprietary and whether it was common enough that outside suppliers could achieve scale or other advantages by supplying it to multiple companies. To determine proprietary value, executives asked themselves two questions:

Did 7-Eleven carry out the capability in a way that generated measurably more value than its competitors could deliver? And would the company suffer a high degree of strategic damage if rivals could imitate that capability?”

The ultimate result was a broad but savvy use of outsourcing and collaboration to cut costs and boost effectiveness. Logistics and distribution was outsourced to a variety of vendors – in one case (fresh prepared foods) slashing those costs from 15% to 10% of sales as a result. It collaborated with a variety of suppliers such as Hershey and Anheuser-Busch to develop new products that were often exclusive to 7-Eleven for a period of time. Citgo, in part a competitor, delivers gasoline to the stores.

One key to the transformation, however, was the way 7-Eleven maintained control over key consumer data: what they are buying by store, the impact of changes in pricing, promotion and in-store positioning, what products sell well together, etc. While this data is shared selectively with suppliers, it is in general viewed as proprietary and a key source of competitive advantage. For example, though 7-Eleven worked with a variety of technology and financial services providers to pioneer a kiosk service that enables customers to cash checks, purchase money orders and other functions, the retailer keeps most of the consumer behavior related to the kiosks private, to protect the insights such information give its executives.

A Framework for Decision-Making

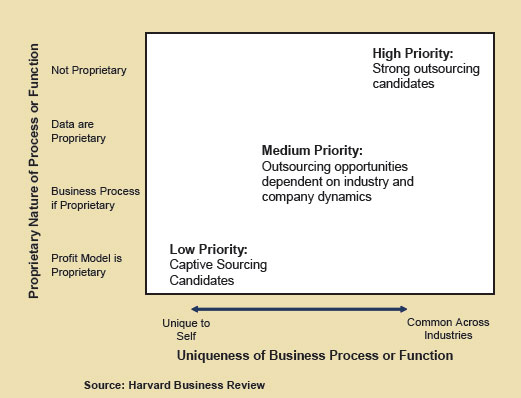

In a 2005 Harvard Business Review article, a trio of consultants from Bain & Company offered a useful model for companies considering capabilities outsourcing. (Strategic Sourcing: From Periphery to the Core, Harvard Business Review, February, 2005). As shown in the accompanying figure, the model suggests that companies should look at a particular process or function across two attributes: (1) the uniqueness of performing the business process itself (i.e., are few or many companies engaged in this function?) (2) how proprietary the process and related data are (i.e., is there competitive advantage?).

By placing a given function or process within this model, companies can get a quick idea of whether that function is a strong, medium, or low priority for potential outsourcing. The challenge, however, is that companies and managers often believe certain processes are proprietary but that are, in fact, undifferentiated.

What are your perspectives on “capability sourcing?” How useful is the framework provided? Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below. |