|

A few weeks ago, I wrote a column on supply chain metrics, with this as the basic thesis:

Many if not most companies, certainly the larger ones, have developed very sophisticated processes for both setting goals/KPI targets and proactively monitoring performance against those goals. If you as a supply chain executive or manager don't hit those goals, it won't be very long before you are "looking for other opportunities," as they say.

Gilmore Says: |

If there was a way to actually get at goals and KPI targets across companies, I suspect that it would look much like a bell curve. And the KPI curve naturally enough becomes the performance curve as well, does it not? If there was a way to actually get at goals and KPI targets across companies, I suspect that it would look much like a bell curve. And the KPI curve naturally enough becomes the performance curve as well, does it not?

Click Here to See

Reader Feedback |

Since I do not see massive turnover in the supply chain ranks, I assume most companies/managers are in fact hitting their targets fairly consistently. Yet, there are a lot of companies overall that are underperforming in the supply chain versus their competition, and study after study has shown a large (and in many cases growing) gap between top and bottom performers.

My logical conclusion therefore was that either those companies are:

1. Being rigorous around the wrong metrics. They are hitting their metrics, but they are the wrong measures.

or

2. The right metrics are largely in place. But the targets are set at the wrong levels.

I said it was probably primarily the latter. Companies set targets that are below what is attainable, often because they just don't know what they could/should be. (See Metrics Strategies and Supply Chain Performance.)

That column generated quite a bit of excellent feedback, enough so that if we get a few more good responses today (hint, hint) I can probably put a "Readers Respond" column together on this, one of my favorite things ever, since it means I don't have to work too hard that week.

Now, clever readers may have seen that this whole line of thinking is just another side of what I have called the "50 Percent Problem." What is that, you ask?

It is the absolute fact that a strong majority of companies and managers almost always think that there performance is better than average, when in fact by definition half must be below average.

I noticed this first when I was back doing real work for a living, and company after company I was trying to help sell something to or offering my advice and counsel would invariably say something like "We may not be the very best in [put your area/metric here], but we are probably in the top 20%."

Almost every time.

There were two exceptions. One is when a new executive took over, and he or she might talk about all the problems they were inheriting, and what needed to be fixed. Come back a year later, and they will have been miraculously solved.

The other was when a company was angling for funding for new supply chain technology, and naturally enough the argument goes we can't compete without, and implicitly or explicitly fesses up a bit when showing where they are now versus where they can get to with the improved software or hardware.

That somewhat anecdotal evidence has since been support more quantitatively many, many times since then, based on how companies respond to various studies. Below is an example I used on this topic in 2009.

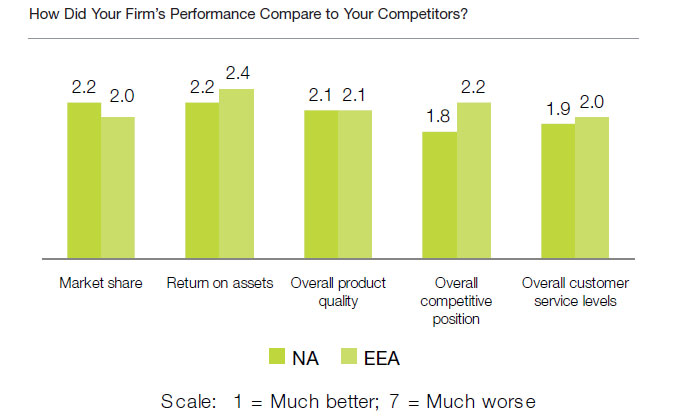

This data came from the well known Trends and Issues in Transportation and Logistics study presented each year at the CSCMP conference. You will note the mean/average response from companies rating themselves against the competition across all four of these categories, on a scale of 1-7, is right around 2.0; whereas, in fact, the mean ought to be around 3.5. If it was 3.2 or something, I would say fine, but from a statistical perspective (and this report had 800+ survey respondents), average scores near 2.0 are simply totally out of whack. Like the parents of the children in Garrison Keillor’s Lake Woebegone, everyone believes they are well above average.

I have seen many other studies showing the same type of result time after time.

And how can this be? The natural and maybe unavoidable tendency we almost all have of thinking we are better than we are in our personal and business lives is surely at work. But could it also be that we think we are performing better than average because, going back to the initial point above, that we are consistently hitting our goals and objectives?

Maybe so. If there was a way to actually get at goals and KPI targets across companies, I suspect that it would look much like a bell curve. And the KPI curve naturally enough becomes the performance curve as well, does it not?

Another Perspective

My thoughts on metrics targets being set too low as a key factor in the supply chain performance differences between companies came upon me a couple of months ago, and somewhere along the line I bounced the idea off my friend Dr. Jim Tompkins, CEO of Tompkins International.

He largely agreed with me, but as usual had his own unique perspective on this. He said companies can come at metrics from three levels:

1. Internally focused metrics and KPIs

2. Measure your own performance based on the metrics your customers use to measure you (which one very well known company is sort of doing but which for now I have agreed to not talk about it publicly).

3. Jointly develop and track metrics with your customers, which Tompkins believes is the absolute right way to go and will lead to the greatest long term supply chain success.

In support of my overall argument, Tompkins told me that the process often works like this: transportation costs are going up at Acme Inc. Directives to reduce transportation costs are issued. The director of transportation suggests and agrees to goals in some area that seem directly related to transportation costs that he or she is highly confident can be obtained and which will seem to indicate that real improvement has been made.

The point is that maybe these targets should have been in place at the beginning. And that focusing on some specific measures may actually cause problems in other areas or not really get the company where it wants to go.

Tompkins says it is critical that KPIs should "get the right focus on "the big things,” and that too often, supply chain KPI’s tend to look only a "the small things."

"For example, a DC Manager gets given the goal of shipping 98% or all orders on time. The on time definition in the company is if the orders are in by 4PM they must go the same day," Tompkins said. "The DC Manager accomplishes the goal of 98% but the customer expectation is not the same day shipment and the way the DC Manager accomplishes the goal is by working 20% more overtime than budget. The result is the DC Manager gets a bonus for achieving their KPI, but the company does not hit budget. Etc."

He says there are hundreds of examples of these types of broken KPI’s, and that it is the norm to see multiple, conflicting objectives.

"We must guide organizations towards profitable growth and not towards some myopic view of short sighted KPIs," Tompkins added.

So that is another view, and it's hard to argue that conflicting goals and KPIs could be at the root of the issue too.

But I'll still argue the 50 percent problem is alive and well, and that companies need to do more benchmarking to better understand where their targets should really be set.

What are your thoughts on the relationship between metrics, reporting, and performance? Do you agree with Gilmore's conclusion that the key difference in performance between similar companies often may be that the targets set are very different? Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below.

|