|

It's the Labor Day holiday this Monday in the US. Just FYI, this now national holiday started as a local event in New York City in 1882 under the direction the Central Labor Union.

It expanded from there rather quickly to other cities and states as formal legislation in an effort to celebrate a "workingman's holiday." National Labor Day legislation was passed by Congress in 1894.

Canada also has a Labour Day on the same Monday as the US. Not sure about other parts of the world.

It's a slow week here and many will be off Friday when this newsletter is delivered, so I decided to take a bit of a look at a number of issues and trends related to "labor," which for these purposes will generally mean "blue collar" labor in the supply chain in manufacturing, distribution, logistics, etc. Right now, there are a bushel basket full of those issues. And supply chain, like it or not, is in the middle of the mix, both at any individual company and as a nation as a whole (and that applies to virtually every economy out there, especially the G-20 nations).

Gilmore Says: |

Earlier this year, giant Asian contract manufacturer Foxconn said that even in its low wage factories in China, it was planning to replace men with machines. Earlier this year, giant Asian contract manufacturer Foxconn said that even in its low wage factories in China, it was planning to replace men with machines.

Click Here to See

Reader Feedback

|

"Labor" is generally having a tough time right now, and many (including myself) have had issues with the union approach in many areas over the years, dating back to my first real job after college at a manufacturing company where the union blocked a move to have factory workers inspect their own work. That company was large enough to survive that brain dead position, but I try to put myself in the shoes of a smaller company where that kind of resistance to continuous improvement could cause real pain.

That said, none of us of course like seeing the devastating loss of manufacturing jobs or high levels of unemployment among blue collar workers. The state of Ohio in which I live has been especially hurt by these kinds of developments, as have many others or even most states.

The reality is the percent of workers in unions in the private sector continues to decline, and rather dramatically. In 2010, 11.9% of all workers, or about 14.7 million employees, were in a union. In 1983, the first year this data was collected, the comparable numbers were 20.1% and 17.7 million workers over a smaller population/worker base. As most know, the percent of union workers in the private sectors is now amazingly low, down to just 6.9%.

Even in manufacturing, the unionization rate is only 10.7%. In "transportation and warehousing," the figure jumps to 20.5%, which would include things like airline pilots as well as truck drivers. Not sure what percent of warehouse workers are unionized, but I am sure it is much lower than 20%. In manufacturing, only about 1.4 million workers are now union members, out of some 13.2 million in total. This is quite an astonishing turn over a few decades.

There are so many dynamics here it is hard to know where to start. One place might be that heavily unionized states (Michigan, Ohio, New York, etc.) have been losing manufacturing jobs and at least relative if not absolute population to "right to work" states in the south and southwest that are less sympathetic to labor, impacting not only manufacturing strategy and jobs but the demographics of the country itself (see Texas).

Unions in manufacturing have been under much pressure for a decade or more, especially as foreign auto companies (Mercedes, BMW, Hyundai, Subaru, Nissan) took the southern route. Even those auto OEMS that had mixed geographic strategies like Honda (Ohio) and Toyota (Kentucky, Indiana, Texas) did so in non-union plants (though paying close to equivalent wages, but without the work rule nonsense).

As I wrote at the time, a seminal change occurred in 2007-09, when bankrupt auto parts maker Delphi (spun out of GM) played hardball with the UAW and was able to extract significant concessions from the union as part of its Chapter 11 exit plan. A big part of that was adopting a aggressive tiered wage system, where newer and less tenured workers made far less than experienced employees.

Tough guy Delphi CEO Steve Miller rather boldly said at the time said the UAW simply had to get real about what it cost to make product worldwide. He wound up compromising a bit, but I believe it was watershed moment that really took the wind out of the labor movement and led to similar changes at GM, Ford and other automakers, which in the end affect other union contracts. The union trajectory had been changed.

Of course, you can still hit the union jackpot. Senior UAW workers still make a very nice living compared to most of their union brethren. Get lucky enough to get a port job on the West coast and join the Longshoremen's union, and you could be pulling down well over $100,000 a year for moving cranes and containers.

Neither of the above is a value statement. Just that this discrepancy between blue collar union wages is not exactly logical. You can pull down $125,000 a year if you are working in the Port of Tacoma, and perhaps $30,000 a year at a factory in Tennessee. White collar salaries for similar work actually have a much tighter range for similar job levels.

Today, all of this is tied at the hip to globalization, and it is somewhat amazing to me that the impact of globalization on US wage compression is not more discussed. Manufacturing wages has been flat at best in real terms for many years. This is clearly largely a function of pressure from low cost overseas goods, and has resulted in both the obvious run to offshore manufacturing and wage stagnation in the US.

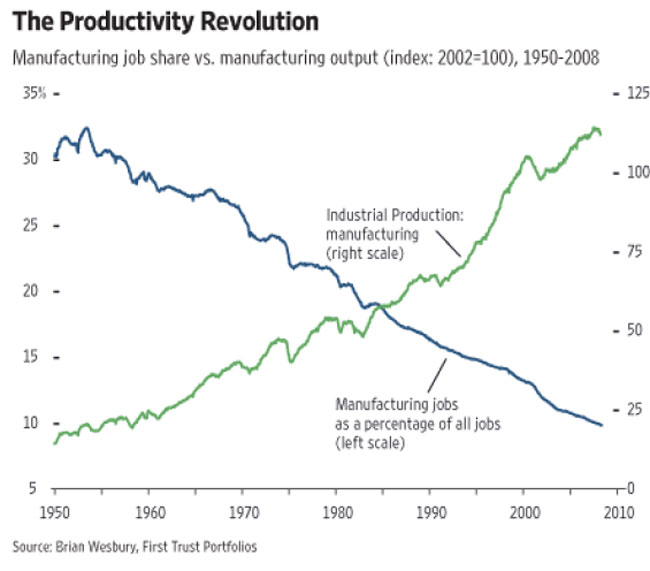

Historically, manufacturing wages were connected to productivity growth, and the rates of such productivity expansion in the US have been the world's envy for a century. But globalization has cut that connection. There is clearly a direct correlation between productivity growth in manufacturing and the amount of manufacturing labor needed, but, unlike most of our history, that has not led to comparative wage increases for those still employed in manufacturing.

The graphic below is very interesting. US manufacturing output, even with offshoring, continues to rise steadily, but almost in the exact oppositetrend for manufacturing jobs.

There is so much more we could discuss. The aging demographic of blue collar workers in trucking, manufacturing and distribution is one area we'll save for later. Not unrelated to that trend is the continued and increasingly aggressive investment in robotics and other forms of automation.

And that is not only in developed countries. Earlier this year, giant Asian contract manufacturer Foxconn said that even in its low wage factories in China, it was planning to replace men with machines. "Foxconn will replace some of its workers with 1 million robots in three years to cut rising labor expenses and improve efficiency," its CEO recently said.

As we have noted many times before, a not well understood megatrend is the rapid rise of robotics in distribution center environments, which will change the face (and labor supply chain) in distribution over the next decade. Until now, automation really had a limited impact on DC labor. That is changing.

What it couldn't get through legislation (card check rule), the Obama administration and the National Labor Relations Board are trying to achieve by other means. First is the outrageous move by the NLRB to block Boeing's move to begin operations at a nearly complete airplane factory in South Carolina, on the grounds that company is illegally retaliating against the unions in Seattle for previous strikes. This issue is now being litigated. Big impact if it goes the NLRB's way.

The NRLB is also proposing a number of rules that appear to give advantages to labor in unionization drives, and challenging states that have implemented laws designed to bar card check provisions were they ever to be passed in Congress or somehow required through NLRB rules. Outcomes of all this totally unknown at present. 2012 election will loom large.

Right now, we are at the shoot out at the OK Corral. It would be so nice if we could bring back the 1950s where companies could succeed and blue collar workers make a nice wage, but we are in a very different place here in 2011.

What is your take on the current "labor supply chain?" Any reaction to Gilmore's perspective? What are other key issues? Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below.

|