|

Do we often make supply chain management harder than it needs to be?

That’s the one of the key takeaways I have as I just finished reading The New Supply Chain Agenda, a new book from three of the supply chain’s most well known names: Reuben Slone, Paul Dittmann and the late John Mentzer.

Slone is currently executive vice president of supply chain at OfficeMax. Dittmann came back to academia a few years ago and now fills several roles at the University of Tennessee. Mentzer, who died late last year, was a professor at the University of Tennessee, and one of the industry’s most prolific and well-known academics. I knew Mentzer the best of the three, but have interacted with Slone and Dittmann a few times as well, and can say that each of the trio has a deserving place at the top of the supply chain though leadership ranks.

Gilmore Says: |

What such a mission says, of course, is that you can't just move along the traditional cost-service curve, but must fundamentally shift the curve in your favor. What such a mission says, of course, is that you can't just move along the traditional cost-service curve, but must fundamentally shift the curve in your favor.

Click Here to See

Reader Feedback

|

All three have a connection to Whirlpool Corp., where Slone and Dittman were both supply chain executives at one point and Mentzer served on the board of directors. They have collaborated before, such as in the well noted 2007 article in Harvard Business Review titled Are You the Weakest Link in Your Supply Chain, targeted at CEOs. That article in a sense was a precursor to the new book.

So what is “the new supply chain agenda?”

It’s a theme we have certainly well-covered here at Supply Chain Digest: better alignment of the supply chain with overall corporate strategy, and more specifically finding and driving the metrics that truly improve shareholder value.

While clearly there has been much emphasis and progress over the past decade on supply chain managers better understanding the language and drivers of corporate financial performance, and company executives better understanding the ways supply chain can effect that performance, many still have a long way to go, according to the book.

“Most CEO’s intuitively know that economic profit drives shareholder value,” the three authors say. “But many don’t clearly comprehend the linkage that begins at supply chain excellence and continues to shareholder value via economic profit.”

The key term there is “economic profit,” which in summary means you are making enough money to more than cover your cost of capital and meet shareholder expectations for returns. It has ties to the well-known Economic Value-Added or EVA approach developed more than 20 years ago, and differs from regular profit in that it accounts for the investment and assets required to generate a given level of profitability.

So, two companies with identical profit levels on the income statement can have very different economic profits – and supply chain performance can often explain much of the difference. (Again, this is a theme we have explored many time – see for example The Real Value of (Less) Inventory.)

There has clearly been something of a sea-change in the way companies now look at inventory, which ties up working capital in addition to masking a variety of supply chain ills. (I liked this quote cited in the book: “Working capital is the capital that doesn’t work.”)

The book cites research from analysts at Credit Suisse, for example, that shows how retailers with outstanding supply chains also have better returns on capital and operating margins. It also cited how some investors made a killing in the 1990s by realizing Target Corp.’s nascent supply chain transformation – moving to a high velocity flow-through distribution model – would surely lead to dramatically lower operating costs and (critically) much improved cash flow for the retailer. Target’s stock value subsequently exploded. While supply chain wasn’t the only factor, it was an important one.

Of course, there may be some challenges to supply chain executives when a CEO finally “gets it.” The books notes one retail CEO who told his head of supply chain that “I want the highest possible availability with the lowest inventory investment and lowest possible logistics costs.” Of course, there may be some challenges to supply chain executives when a CEO finally “gets it.” The books notes one retail CEO who told his head of supply chain that “I want the highest possible availability with the lowest inventory investment and lowest possible logistics costs.”

Well... how’s that for a challenge? (I am speculating this actually was the directive Slone received from his CEO when he took the OfficeMax job a few years ago – a goal he has well delivered.)

What such a mission says, of course, is that you can’t just move along the traditional cost-service curve, but must fundamentally shift the curve in your favor.

When I wrote at the beginning of this piece that this book made me think we often make supply chain harder than it needs to be, that notion came from the five steps Slone, Dittman and Mentzer identify as key to meeting the challenges of the new SCM agenda.

Those five steps to achieving supply chain excellence are:

- Pick the Right Supply Chain Leaders and Develop Supply Chain Talent: It’s the leadership and people that make the difference in the end.

- Keep Up with Supply Chain Technologies and Trends: Be more in tune with what’s out there – and just as importantly take more advantage of the capabilities you already have.

- Eliminate Crippling Cross-Functional Disconnects: The toughest of the five, in my opinion, even though supply chain at its core is cross-functional. But getting the right metrics and incentives in place can go a long way to addressing the silo challenge.

- Collaborate with Suppliers and Customers: SCM leaders must regularly meet one-on-one with their trading partner peers – and understand the biggest barrier to collaboration is often the company itself.

- Implement a Disciplined Process of Project and Change Management: “Without a disciplined process to get things done, everything else becomes irrelevant,” the book says.

Obviously, there is a lot to meeting each step, and the majority of the book is about how to get it done. Still, it seems to me that if supply chain leaders simply focused part of every day each per week on these five steps in sequence, some very good things would start to happen. We too often get lost in all the complexity that can be found in our supply chains.

The book also contains a simple diagnostic that asks supply chain executives and managers to grade out their supply chain performance on a scale of 1-9 (9 being the best) on some basic questions such as “Do you have a supply chain strategy with the right incentives and metrics?”

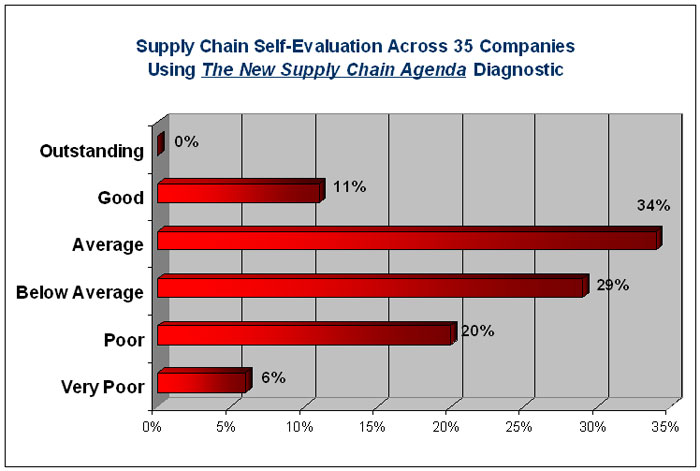

The authors piloted the tool with a group of 35 supply chain executives (likely at a University of Tennessee forum), and I found the results interesting, as shown below.

None of the 35 respondents scored in what the tool considers the “Outstanding” range (48-54 on the total score for the 6 questions, or an average of 8 out of 9 in total). 61% of companies were below average or poor. Just 11% scored out as “good,” with 34% coming in as “average.”

I don’t know if this is generalizable or not, but I suspect largely “Yes” – meaning most of us still have lots of opportunity to improve our supply chains.

There is much more in the book of course, which actually is a quick and easy read. The bottom line: the “new agenda” is for companies to better connect supply chain performance, metrics and language to the boardroom, and focusing on just five supply chain fundamentals may be enough to get it done.

What’s your reaction to the “New Supply Chain Agenda?” Can focusing on the five steps the authors identify enough to get it done? What would you add or change? Is the new agenda to better connect SCM and the boardroom? Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below.

|