|

I will admit to being somewhat overly focused on the "supply chain of the future?"

Why? Several reasons.

First, I really believe we are on the cusp of new, dramatically different levels of automation, in everything from case picking in distribution centers to real-time supply chain decision support, that will have a game-changing impact on supply chain practice.

Gilmore Says: |

I believe most of us can agree that the supply chain of the future is going to require very different skills sets among executives and mid-level managers than have been needed the very recent past. I believe most of us can agree that the supply chain of the future is going to require very different skills sets among executives and mid-level managers than have been needed the very recent past.

Click Here to See

Reader Feedback

|

Second, I very much like the concept of historical eras and "inflection points." So, my quick summary is that we have seen the foundation era (late 1980s through mid-1990s), when supply chain thinking (cross functional, improving the links) first took hold; the technology era of the mid-1990s through the dot com collapse of 2000-01, when supply chain software took dramatic leaps forward and became seen as essential to supply chain success, to the point of mania in some case.

Next came the Lean/continuous improvement era starting after the tech collapse until the middle of the next decade or so, when we took a step back from technology and focused on process and taking Lean concepts beyond manufacturing; finally, the global/virtual supply chain era from then until now, with a nasty recession in the middle, where being global became critical on both the buy and sell sides of the supply chain, and outsourcing and virtualization, with both their benefits and challenges, driving much of our supply chain strategies.

That analysis is not perfect, there are overlaps, etc., but think it is roughly right.

I think we may see even bigger shifts in the coming decade, largely as noted above stemming from a variety of step-changes in supporting technology (cloud computing, real-time optimization, robotics, visibility) and the impact that will have on supply chain processes and even organizational structures.

All that as an intro into yet another view of the supply chain of the future, this time from the smart folks at McKinsey, the management consulting firm.

Let's take a look.

McKinsey makes a bold statement right up front: "Many global supply chains are not equipped to cope with the world we are entering," McKinsey says. "Most were engineered, some brilliantly, to manage stable, high-volume production by capitalizing on labor-arbitrage opportunities available in China and other low-cost countries. But in a future when the relative attractiveness of manufacturing locations changes quickly—along with the ability to produce large volumes economically—such standard approaches can leave companies dangerously exposed."

Here is a reality McKinsey observes and with which I completely agree: The world is changing rapidly, most noticeably with the rise of emerging economies across the globe, and not just China. That in turn will almost certainly lead to much higher levels of volatility in demand and supply, and greater levels of supply chain complexity than most of us have known to date. It makes perfect sense to argue that most supply chains as currently constructed are not well-suited to this new environment.

For example, meeting increasingly tailored product requirements in a company's home market is tough enough. Now try doing that globally across diverse economies, cultures, religions, etc.

McKinsey offers this factoid as evidence of this global impact: Mobile-phone makers introduced 900 more varieties of handsets in 2009 than they did in 2000. It is likely to get worse before it gets better.

The upshot, McKinsey says, is that for "would-be architects of manufacturing and supply chain strategies there is a greater risk of making key decisions that become uneconomic as a result of forces beyond your control."

I would add a complementary perspective: supply chain network design used to be mostly about the math (optimization) and the ability to drive the optimal solution through the supply chain in a timely manner. Increasingly, it is about how good a company's assumptions are, and managing the trade-offs between cost and flexibility. You place your bets.

The winning formula, McKinsey argues, is a two-pronged strategy:

1. "Splintering” traditional supply chains into smaller, nimbler ones better prepared to manage higher levels of complexity.

2. Using supply chains as "hedges" against uncertainty by reconfiguring manufacturing footprints to weather a range of potential outcomes.

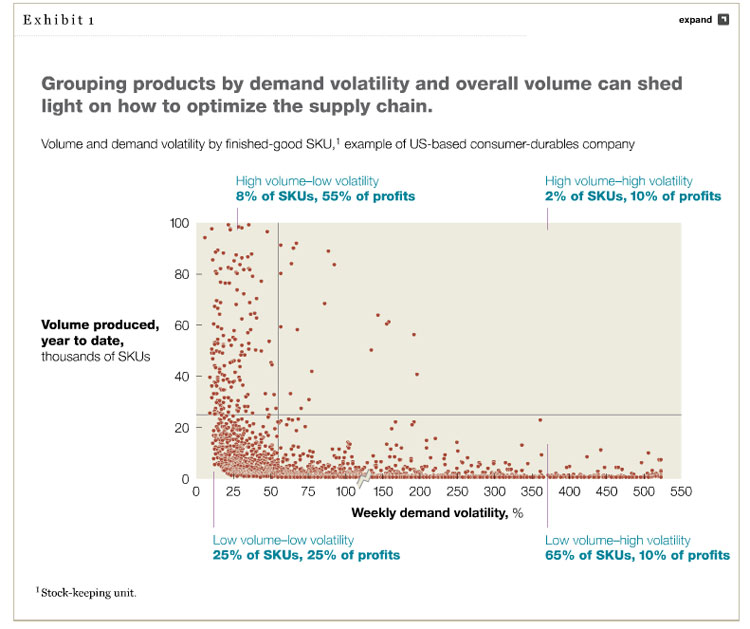

Let's start with number 1. The idea of multiple supply chains has been around for some time and seen a resurgence in the recent past, including a lot of work we have done here. But how do you do that in practice? McKinsey argues that a detailed SKU analysis is a good place to start, such as one consumer durables manufacturer recently did to understand SKU volumes and volatility (see figure below).

Source: McKinsey

After the analysis, the company split its "one-size-fits-all" supply chain, mostly based on production in China, into four distinct splinters. For high-volume products with relatively stable demand (less than 10 percent of SKUs but representing the majority of revenues), the company kept the sourcing and production in China. Facilities in North America became responsible for producing the rest of the company’s SKUs, including high- and low-volume ones with volatile demand (assigned to the United States) and low-volume, low-demand-volatility SKUs (divided between the United States and Mexico).

The bottom line here is that McKinsey says the supply chain winners of the next decade will be those that decompose their supply chains and tailor them to focus on what best meets customer needs at lowest cost based on any number of different criteria, and that doing so will make those supply chain more responsive to change and actually reduce supply chain complexity by the very nature of having this focus.

On to number 2, which is connected to number 1, and goes something like this: in an era of increasing dynamics and uncertainty, having a supply chain that can respond more rapidly than competitors is a significant advantage

The basic concept is similar to "real options theory," which says there is value in investing in a flexibility to take any of several alternatives in the future versus locking in on one choice today. The value of having those future options can be calculated, and compared to the cost of creating those options. Any easy example would be spending extra money today to have additional manufacturing or distribution capacity/space down the road at a given facility.

McKinsey thinks that supply chain agility in this dynamic world is of critical, even existential importance: "The ability of supply chains to withstand a variety of different scenarios could influence the profitability and even the viability of organizations in the not-too-distant future," McKinsey says. Going further, it says that "The goal should be identifying a resilient manufacturing and sourcing footprint—even when it’s not necessarily the lowest-cost one today."

It cites the example of one manufacturer that is creating a supply chain that can quickly make adjustments based on currency and labor cost swings.

So at the end of the day, McKinsey says that to win in the global supply chain moving forward, companies need to be much better at segmenting their supply chains rather than taking a more universal approach, and that having production/supply chain capabilities in more places than is cost optimal in the short term may be cost optimal in the mid-term based on the added flexibility in this dynamic environment.

I will simply add this. Whether you agree or disagree with this thinking, I believe most of us can agree that the supply chain of the future is going to require very different skills sets among executives and mid-level managers than have been needed the very recent past. Are you ready?

What do you think of McKinsey's two-pronged recommendations? Will companies really accept a higher cost model for now to have flexibility for the future? Is the example SKU analysis shown a good place to start? Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below.

|