| |

|

| |

|

|

Supply

Chain by the Numbers |

| |

|

| |

- June 15, 2017 -

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Amazon Roils the Grocery Sector; Nike Takes a Whack at SKU Counts; Why is US Productivity Flat? Is US Manufacturing Glass Half Empty or Half Full? |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

14.5% |

|

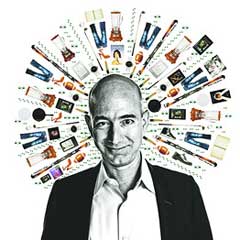

| That is how much Kroger's stock price was down in early trading Friday after Amazon announced it was buying grocery operator Whole Foods for $13.7 billion, in a deal that has been rumored for a couple of years. Supervalu was down even more, at 17%, while Target was down 10% while Walmart 6.7%, though of course things could easily change by end of day. What the impact of Amazon owning a major grocery store network of course remains to be seen. "This is an earthquake rattling through the grocery sector as well as the retail world," said Mark Hamrick, senior economic analyst at Bankrate.com. "We can only imagine the technological innovation that Amazon will bring to the purchasing experience for the consumer." However, apparently a chance another suitor, such as Walmart, could jump into the fray and try to offer a higher price than Amazon has set, which was a 27% premium to Whole Foods existing stock price. This should be a wild ride. |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

That was "value add" of US manufacturing in 2016, according to US government data as summarized in a new report this week from Ball State University Center for Business and Economic Research and Conexus Indiana (a private sector-led initiative focused on the advanced manufacturing and logistics sectors), as is released every year. Whether that's good or bad depends on your viewpoint. That figure is just barely above the $2.08 trillion in value-add produced in 2005, so over more than a decade there has been little manufacturing growth based on that metric, and indeed there was a small dip in the 2016 number versus 2015. However, the data also shows manufacturing isn't in decline in the US, and is up modestly from the recent trough in 2009. And the "real GDP" of US manufacturing, another way to assess its health, paints an even better picture, setting a record last year of $2.2 trillion, breaking the previous record achieved in 2015, but again that number is not much above the $1.99 trillion reached all the way back in 1997. Some publications out there are parroting the language from a press release on the report to say that US manufacturing is "surging" - that is obviously not the case. There is growth, but it is very modest over many years. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

0% |

|

That was the revised level of US productivity growth in Q1 versus Q4 2016, according to new data releases from the Labor Dept. last week, up from -0.6% originally estimated. The story was a little better year-over-year, with growth of 1.2%, matching the average annual rate of growth over the past decade, but well below the 2.6% pace seen in the early 2000s. The persistent lack of productivity growth - how much output is achieved given the amount of working hours - in the past decade in the US and other countries has many economists scratching their heads, though low levels of business investment in new machinery, software and other advances is generally though to be the key issue. Productivity gains are critical to overall economic growth and to rising wages, both of which have generally been weak for many years now. New research from the International Monetary Fund this week says the lack of available credit to businesses and weak balance sheets in the years after the Great Recession in 2008-09 explains abut one-third of the decline in productivity growth, as firms simply lacked the financial wherewithal to make productivity-driving investments. However, that credit picture is changing for the positive - though obviously not showing up yet in terms of productivity gains. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |