Coming out of grad school, I interviewed with three large consulting firms: McKinsey, Booz Allen, and AT Kearney. The latter two offered me a job. McKinsey, to its everlasting detriment, did not. I think I didn't manage my silverware quite right at lunch with two of the partners in the Cleveland office.

I bring that up not only for a small bit of humor, but also because something one of Booz Allen partners told me at the time: that 50% of consulting was usually reminding companies of principles and practices that they knew or lived by at some point but somehow have forgotten.

Gilmore Says: |

Understanding and managing all these rules would be quite a challenge. That one person has put them all in one place is quite an accomplishment. Understanding and managing all these rules would be quite a challenge. That one person has put them all in one place is quite an accomplishment.

Click Here to See

Reader Feedback

|

A few weeks ago, I did a review of Dr. David Simchi Levi's new book Operating Rules: Delivering Customer Value through Flexible Operations. At a high level the main theme of the book is that it is really possible to "engineer" supply chain performance according to core principles and mathematical analysis. I must confess to having read at the time just the first few chapters in detail, and mostly skimming the rest - a long time book review strategy, but even more acceptable this time because I had planned to do a part 2.

So when I went through the bulk of the book in more detail, it hit me in a bigger way that not only does this book as usual with Simchi-Levi offer a wealth of provocative insight, there is also, as the book title makes clear, a large set of rules or principles that can help us effectively govern the supply chain. Some of them we may not know. Maybe even more we simply forgot. What this book does in part is put darn near all of them in one place.

More on that in a minute. But first, our Feedback question after that first piece asked whether readers believed the supply chain really could be "engineered," as Simchi-Levi believes.

Dr. Andre Martin, inventor more than 30 years ago of the concept of Distribution Requirements Planning (see trivia question below) and now at RedPrairie's Flowcasting Group, offered the following Feedback: "Simchi-Levi is theoretically correct. This being said, you need a capability to model the complete supply chain, test for various scenarios, dollarize the results, and then pick the scenario that has the best trade-off."

He offered an interesting example of how one company he was working with was balancing very clear and real trade-offs between inventory and service levels, using the models and the math.

Simchi-Levi responded that "This is no theory - this is practice," asMartin supports with his example. Simchi-Levi does a lot of consulting, from which much of the data and examples in the book have been drawn.

So, back to the rules. Each chapter in the book offers a series of rules along a wide variety of topics, from procurement strategies to supply chain network design. The majority have a mathematical type component to them, though some are more in the nature of principles not necessarily grounded in models or formulas. (Simchi-Levi says in the book that all of the rules have either a mathematical basis or are supported by empirical research.

So, let's take a very simple rule, presented very early on: Rule 2.2: Functional and innovative products each typically require different supply chain strategies. Now, most of us have heard that before or intuitively know it to be true. Yet, Simchi-Levi makes the persuasive case that it is often not well applied in practice. He notes, for example, how products often change over time - today more rapidly than ever - from innovative to functional. Do the supply chain approaches similarly evolve at the same pace?

That begets an interesting discussion on push, pull, and push-pull supply chain strategies, and observations like this: "Everything else being equal, higher demand uncertainty leads to a preference for managing the supply chain based on realized demand: a pull strategy." However, the greater the economies of scale in manufacturing for a product, "the greater the value of aggregating demand, and thus the greater the value of managing the supply chain based on long-term forecast: a push strategy."

That chapter then goes into all the twists and permutations that are actually encountered in real life supply chains, including noting that the whole push, pull, push-pull decision needs to be further broken down into both manufacturing and distribution dimensions. All that leads to Rule 3.2: The appropriate supply chain strategy (push, pull or push-pull) is driven by the level of demand uncertainty and economies of scale, and the book then at a high level shows how that can be mathematically determined.

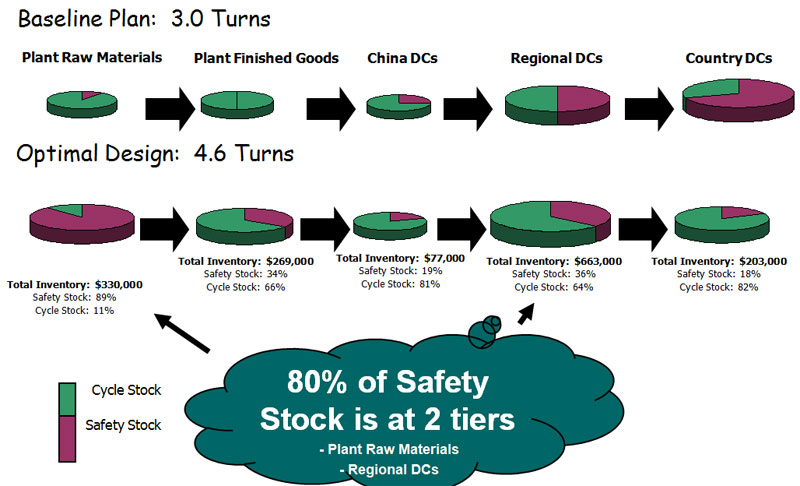

This leads to related rules about supply chain design and inventory positioning. The example below shows how a large metals distributor was able to use detailed modeling and optimization capabilities to increase its inventory turns by 50% through changes in where inventory was positioned in a long supply chain.

The book covers wide ground, with a whole chapter just on rules for procurement, for example. I've known David for a long while, and never knew he really focused that much on that area. He states that "it can be shown that carefully designed supply contracts can achieve the exact same profit as 'global optimization,'" which he defines as the state in which total profit across the supply chain is maximized, but something that can't be achieved in practice because of cross interests and reluctance to cede control.

Understanding and managing all these rules would be quite a challenge. That one person has put them all in one place is quite an accomplishment. I wish there would perhaps have been more discussion in the book about how using many of the rules together might lead to some conflicts. But perhaps we'll have a chance to discuss that on a new Videocast series that Simchi-Levi has agreed to do with SCDigest. You can learn more and register at this link: Operating Rules Videocast.

One thing I can definitely say is that if I was a chief supply chain officer, I would have my admin type up each rule in the book in one relatively short document. I would then see which ones we perhaps should be considering that our supply chain currently does not, and maybe more importantly use it as a reminder, when it is time for a decision, of the core principles of supply chain that so often get lost in the heat of battle.

What do you think of a compendium of dozens of "supply chain rules?" Why is it so easy to forget core principles? Can we use rules and math to better engineer supply chain performance (we ask again)? Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below. |