The first place to find the right supply chain answers is to ask the right supply chain questions.

The ability to do that in provocative ways has always been one of the hallmarks of my friend Dr. David Simchi-Levi of MIT, who is back with a new book that continues as usual to add substantially to the supply chain body of knowledge.

It's titled Operation Rules: Delivering Customer Value through Flexible Operations, and while the book covers a lot of ground, there is one overriding theme: many companies don't do a great job of matching supply chain/operations strategies with their core business strategies and customer value proposition. Getting that right can lead to game changing market success.

Gilmore Says: |

There really are "universal laws" that apply, Simchi-Levi says, governing such things as the relationship between variability and supply chain performance, inventory and service levels, flexibility and cost, etc. There really are "universal laws" that apply, Simchi-Levi says, governing such things as the relationship between variability and supply chain performance, inventory and service levels, flexibility and cost, etc.

Click Here to See

Reader Feedback

|

There are some obvious examples of how this works in practice. Simchi-Levi cites WalMart's core value proposition as being Every Low Pricing, with a corresponding supply chain strategy of maximizing cost efficiency. (It's no coincidence that the substantial drop in WalMart's stock price in the middle part of the 2000s was correlated with a period where the company let inventories substantially bloat, leading to several successful strategies to reverse that inventory trend).

One of the core truths that sometimes supply chain professionals conveniently pretend isn't there is the fact that there is a fundamental trade-off between speed and cost. A company that seeks to maximize supply chain "responsiveness" will generally incur higher operating costs than a competitor that primarily looks to optimize supply chain cost over speed.

"One important challenge is that although seasoned operations and supply chain executives understand the differences between efficiency and responsiveness, many are confused about when to apply each strategy," Simchi-Levi writes. "Worse still, senior managers typically spend a considerable amount of time and energy on customer value, but they may be ignorant about the connection between the consumer value proposition and operations strategies."

The core question becomes: "What should really drive operations and supply chain strategies, given the inevitable trade-offs that exist for different paths?" I am not sure that many companies specifically ask or answer that question.

Based on his insight, direct consulting experience, and supporting quantitative research, Simchi-Levi says there should be three inter-connected drivers of supply chain strategy:

- Customer value proposition

- Channels to market

- Product/product lifecycle characteristics

What separates this book from much other supply chain thinking is that Simchi-Levi recognizes that it's not that simple or clean in practice, however. For example, a product's characteristics may offer mixed signals. What separates this book from much other supply chain thinking is that Simchi-Levi recognizes that it's not that simple or clean in practice, however. For example, a product's characteristics may offer mixed signals.

"Often, managers find that some product attributes push the operation strategy in one direction while other attributes pull the strategy in a different direction," Simchi-Levi writes.

And of course, in total a company may have a number of different customer value props, channels and product characteristics, which in theory should have different types of supply chains.

"So what is a company to do? Should operations establish a single supply chain? Which one? Alternatively, if the firm is to establish multiple supply chains, is there a way to take advantage of potential synergies between the various supply chains, or should the different supply chains operate totally independently," Simchi-Levi questions early in the book. Again, the fact that the book is willing to take on and answer those tough questions is part of what makes it an important contribution to the profession.

Conflicting Objectives?

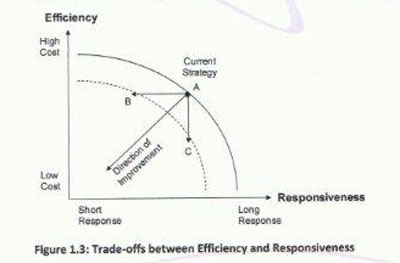

We've all seen various trade-off curves, and Simchi-Levi offers what he calls an "efficiency curve" to illustrate classic supply chain trade-offs, as shown below.

Most of us, I think, look at these trade-offs in a very basic way. That is, we understand that to achieve a bit of cost reduction, we may have to give up a bit of responsiveness. But Simchi-Levi says the efficiency curve and trade-offs are in fact fundamental to supply chain strategy. In other words, how close a company gets to making these trade-offs exactly right - depending on customer value prop, channel strategies, and product characteristics - will largely determine the success of a company's supply chain, and result to leading, middling, or laggard performance, depending on the degree of fit.

But, as the graphic implies, it may also be possible to actually shift a company's existing curve, making a step change in supply chain performance from the outer curve to the inner curve, getting more efficiency and responsiveness at the same time.

In turn, getting the strategy fit right "requires a shift from "best practice" to a more systematic and scientific approach that links customer value, product characteristics, and marketing channels directly to operations strategy," SimchI-Levi says.

That is a very provocative statement - that choosing the right supply chain strategy at a given point in time can be determined scientifically. Hence, if it isn't obvious, the title of the book: Operation Rules. It is possible, indeed essential, Simchi-Levi says, to "engineer" operations and supply chains in a different way than most of us think about such things.

Ignore these rules "and you will find yourself heading towards failure; follow them and you will steer yourself away from problems and towards and operating strategy that drives real business value," Simchi-Levi posits.

How is it possible to engineer the supply chain? There really are "universal laws" that apply, Simchi-Levi says, governing such things as the relationship between variability and supply chain performance, inventory and service levels, flexibility and cost, etc.

Those mathematical tools can be then combined with the supply chain needs of different customer value props, channels and products, and the use of a menu of tactics that include optimizing push-pull boundaries, use of postponement strategies, investment in flexible manufacturing and more that lead to the right supply chain strategy in total.

If that sounds like a comprehensive model, it is. How does it really come together, and how can this approach really be used by companies today?

Alas, I am out of room. How is that for a tease? I will have part 2 of this review and comment in a couple of weeks. Until then, consider the book. I highly recommend it.

What is your take on the thesis of Operations Rules? Do you think our supply chain can be better "engineered?" What are the challenges you see, or have you taken such an approach? Let us know your thoughts at the Feedback button below. |